The last day of 2011 brought a welcome surprise – an email from a research professor at the University of Aarhus in Denmark. He was writing to thank me for submitting a report of a Canada Goose that his team had banded in the summer of 2008 in a remote part of Western Greenland.

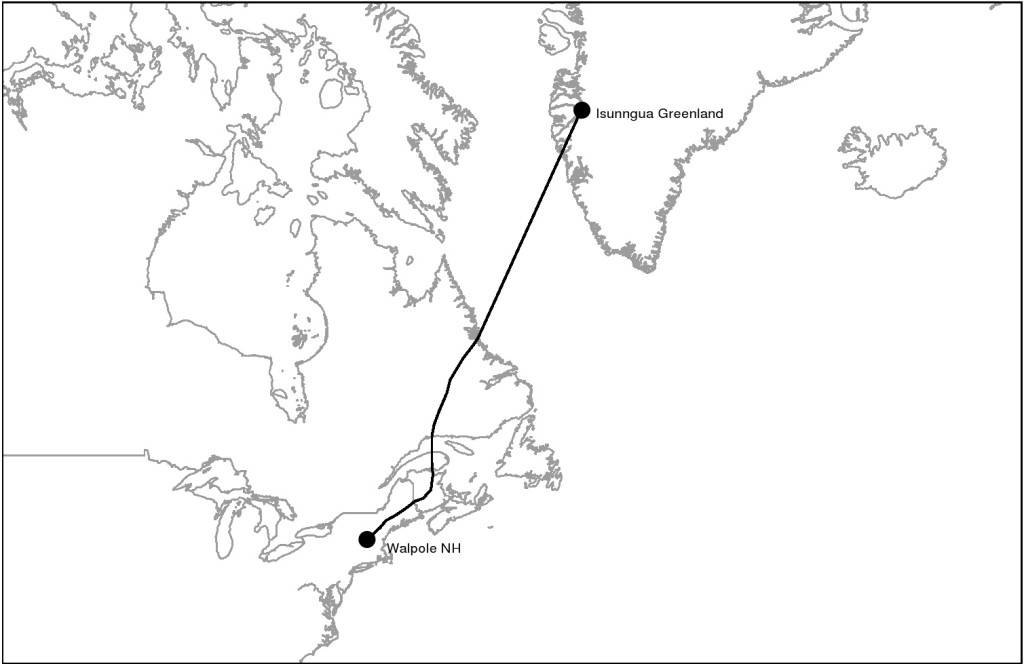

I saw the goose in a stubble field in Walpole on March 22 of this year, at the time an unremarkable goose amongst geese, except for a large yellow neck collar inscribed with the letters GJN. The purpose of a neck collar is to enable the letters to be read without having to catch the bird – leg bands are rarely field readable. I sent the data off to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, which coordinates band recoveries and field sightings in North America and promptly forgot about the bird until the e-mail on New Year’s Eve.

GJN with Canada Geese and a few Greenland Greater White-fronted Geese, Isunngua, Greenland, July 22, 2008.

Canada Geese can be found in New Hampshire year round, but they become quite scarce in southwest NH during the winter freeze. In March and April they pass through the state by the tens of thousands, destined for breeding grounds further north. They are a widespread species, comprising multiple forms that breed across a large part of the United States and most of Canada. The geese that pass north through New Hampshire in spring might be destined for breeding grounds in Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Labrador, or as far north as Greenland. Unless a bird is marked like GJN, which was banded in Western Greenland on July 17 2008, we don’t know an individual’s final destination.

It is one thing to understand in the abstract that Canada Geese breed in Greenland and another thing entirely to see a goose in a field in Walpole and subsequently discover that it was born two time zones away, a distance of about 3,500 miles across three countries. The New Year’s Eve missive from Denmark distilled my bookish fascination with bird migration onto a real live bird, as if this goose had flown straight off the set of the film Winged Migration. Through wonderful moments like this, all the incredible stories that I have read about bird migration take form.

Not all the Canada Geese in New Hampshire are as well traveled as GJN. The geese that stay with us during the summer months come from stock from the mid-western states and were introduced to the northeast to augment the population in response to declining stocks elsewhere. They have subsequently lost the urge to migrate, and have become so common that they are regarded as a nuisance in places. This does a disservice to the truly wild creatures we see in spring. When next you spy a “common” Canada Goose, ask yourself whether you might be looking at one destined for Greenland, and allow yourself to be a little awestruck. Happy New Year!

Update – I resighted this exact same bird on March 29 this year less than three miles from where I saw it in 2011, and this time I got a documentation photo (though at 1/4 mile distance, its not Nat. Geo. quality). It’s been back to Greenland twice in the meantime, dodging Gyrfalcons, buckshot, and countless other hazards. Truly great to see it again.

One Response to “A Goose Story”